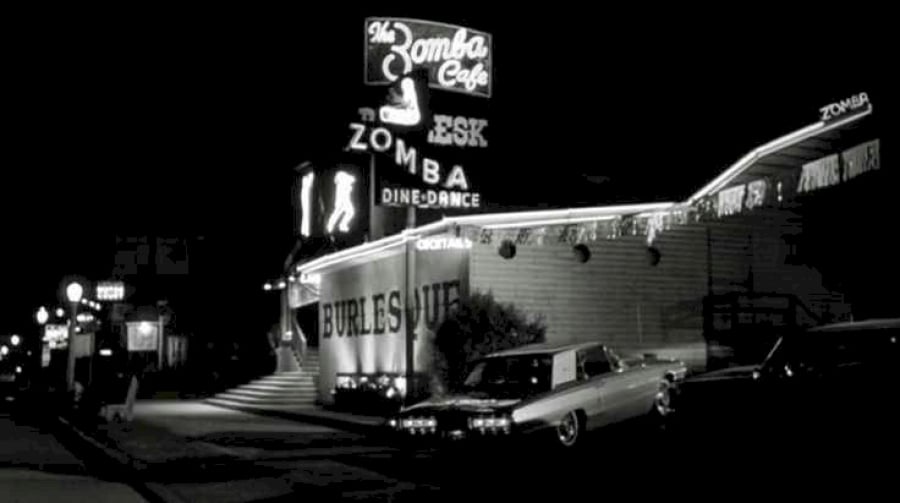

Before Oil Can Harry’s opened in 1968, The Zomba Cafe, an upscale burlesque theater, operated at 11502 Ventura Blvd. Photo: Courtesy of Oil Can Harry’s.

Tommy Young remembers the first time he went to Oil Can Harry’s.

It was April 19, 1986.

For Young, Oil Can Harry’s was more than a gay nightclub. Young says he had never felt so safe in his life.

“I had been running away from things all my life,” says Young, 60, who was born and raised in England. “I was molested, turned to prostitution, grew up in battered women’s shelters. When I walked into Oil Can Harry’s, I lost all that bad energy. The people were amazing. It was a family place. They were my family.”

Oil Can Harry’s had a retro and country Western vibe. It was the longest continually operating LGBTQ club in Los Angeles, and possibly West of the Mississippi.

The Studio City-based club opened in 1968 and continued to operate until it became a COVID-19 casualty in January.

That first night Young walked through the doors, it was rodeo night at Oil Can Harry’s, and the crowd was country line dancing.

“When I saw country line dancing, I had never seen that before,” Young says. “It was a wonderful acceptance of gay people. I came from England. I was beat up, and called names. Being accepted was wonderful.

“Oil Can Harry’s gave me a sense to be who I was. It gave me a sense of being. It gave me life basically,” Young says. “It served that purpose for many years.”

Young also worked at Oil Can Harry’s more than 34 years, including 25 years as lead bartender and event planner.. During his first night at the club, Young was offered as job as a bar back, and accepted it.

To the patrons who frequented the 52-year-old historic gay watering hole, which was renowned for it’s Friday night country line dancing or Saturday night disco parties, it was more than a bar or a dance club. It was a safe space.

“It was a community. Throughout all these years, that’s where people met their boyfriends, made new friends,” says Rick Dominguez, 56, who was the club’s resident DJ since 1993. “I attended hundreds of weddings of gay couples who met at the club.”

The club’s early days coincided with the dawn of the LGBTQ civil rights movement and sexual revolution. It also was the days of Donna Summer, Thelma Houston, and Gloria Gaynor, whose disco hits caused many fanny bumpers on the dancefloor.

In Los Angeles and the Valley, people felt freer and safer to frequent gay spaces not located in an out-of-the-way industrial area or down a dark alley and hidden behind a nondescript door.

“During the 1970s and 1980s, it was superstardom with lines of people up the street,” Young says. “People would call asking what was a good time to arrive, and we would say, Get here by 9 p.m. or you won’t get in.”

If those walls could talk, they would share more than five decades of LGBTQ history. (A process is underway to have the site designated a cultural-historic monument.)

Instead, here are seven things you didn’t know about Oil Can Harry’s.

The early years

The parcel at 11502 Ventura Boulevard has been a hotspot for nightlife since 1936, when it was home to Rex’s White Cabin, which served food and had dancing, according to Mary Mallory. In 1939, the Everglades debuted on the site, and in 1941, Zomba Cafe, an upscale burlesque theater, opened its doors.

Bert Charot bought it in 1967 and opened Oil Can Harry’s in 1968. “Bert knew the woman who owned Zomba Cafe,” Young says. “She lived upstairs from the club, and Bert said she had these huge cages filled with doves.”

Charot, who identified as gay, was nicknamed Sonny Bono because he looked like the singer-actor.

“Everybody thought he was Sonny Bono,” Young says. “There was a resemblance. People would say, Is Sonny Bono here?”

At one point, Charot and his brother, nicknamed Mouse, also owned two other Oil Can Harry’s locations: San Francisco and Cathedral City.

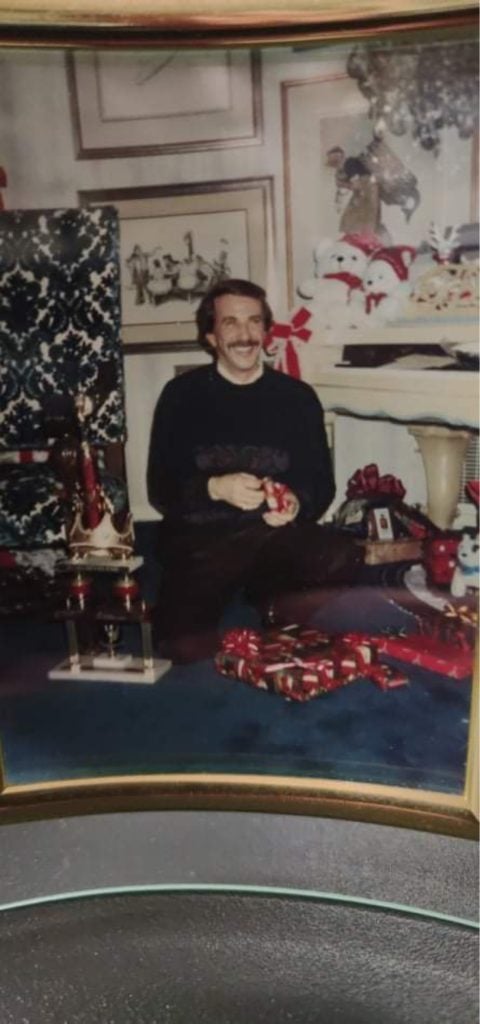

Bert Charot was the first owner of Oil Can Harry’s. His nickname was Sonny Bono because people thought he resembled the actor. Photo: Courtesy of Jerry Arko.

Oil Can Harry’s name and logo

“Bert and Mouse collected a bag of names that people had written down. They took five names out of the bag and put them into a bowl and shook it up,” Young says. “The name they selected was Oil Can Harry’s. It sounds corny, but it’s true.”

The name of the character in the logo is Oil Can Harry, with his signature stovetop hat, handlebar mustache, and tuxedo.

“He was always described to me as a villain,” Young says. “He’s like the villain Dick Dastardly in ‘Wacky Races,’ who had a little dog Muttley. It was based on a character like him.”

The animated TV series “Wacky Races” debuted in the fall of 1968 and lasted 17 episodes. The Dick Dastardly character appeared in other cartoons, including “Dastardly & Muttley and Their Flying Machines,” which debuted in the fall of 1969, among others.

A peep hole in the front door

Oil Can Harry’s front door had a peep hole that, back in the day, let people see if the Los Angeles police were trying to come in and raid the place. In the 1960s and 70s, Los Angeles had an ordinance that made it illegal for same-sex couples to dance together.

Also, a siren inside the club was used to warn patrons if the police were about to enter the building.

“In the early days, you rang the doorbell, and people would look to see who it was. You couldn’t just walk into the club,” Young says.

“Mainly, that was for the police. If the person at the door looked and saw the police, they would signal to the DJ, who would turn on the siren, which also had a blue light,” Young says. “People would then change partners or stop dancing together. Everybody knew what was going on.”

By the time Young worked at the club in 1986, Los Angeles had abolished the ordinance and police raids had stopped. But the siren was still used.

“While everyone was dancing to Donna Summer or country line dancing,” Young says. “They would play the siren to celebrate having a great time.”

Hosted fundraisers to combat HIV

During the 1980s and 90s, as the virus ravaged the gay community, Oil Can Harry’s hosted numerous HIV fundraisers. Charot and manager Bob Tomasino were committed to fighting HIV-AIDS.

“There were so, so many people who died. They were in the middle of it all,” Young says. “Not only were customers getting sick and passing away, so were the staff. It meant a hell of a lot to them.

“They felt this was their mission to do,” Young says. “They didn’t want their names put into the mix. They didn’t do it so people would say, Oh. Aren’t they nice.”

“Bob Tomasino was one of the most kind and generous men I’ve ever met,” Young says. “He was dedicated to the cause. If you needed something, he would find a way to get it.” After Charot died in 2007, Tomasino and his partner, John Fagan, bought Oil Can Harry’s in 2008. They married that same year. When Tomasino died in 2013 at the age of 66, Fagan took over the bar until it closed this year.

ACT-Up protest

In the early 1990s, ACT-Up protested at Oil Can Harry’s because lesbian patrons said the club’s manager was hostile toward them. Nobody had reported any previous problems, but Young had witnessed the behavior.

“They couldn’t dance on the carpet. They couldn’t put their coats here. Whatever they did, it was just wrong,” Young says.

“I was told, Don’t smile at the women. Don’t say goodbye or thank you,” Young says.

A short time later, customers pushed back.

“We had a huge protest at the bar. ACT-Up was there, everybody was there,” Young says.

Charot, the club’s owner, stepped in. When he became aware of the manager’s instructions to Young about being rude and hostile toward the lesbian customers. Young didn’t follow the orders.

“Bert heard about this and said, Tommy, keep doing what you are doing. You will not be fired,” Young says. The manager was let go.

2019 Grammy after party

On Feb. 10, 2019, a Grammy afterparty was hosted by Mark Ronson, the multi award winning songwriter-producer who also won an Oscar, a Golden Globe Award, and Grammy for writing “Shallow” (performed by Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper) for “A Star is Born.”

Guests included Adele, Katy Perry, Lizzo, and Lady Gaga, who also performed.

“Mark had come to Oil Can Harry’s with friends and really loved the vibe and the retro look,” Dominguez says. “He had a vision for a theme party in the atmosphere in Oil Can Harry’s. They turned it into the Broken Hearts Club.

“It was a blast. Gaga hung out with us in the DJ booth,” Dominguez says. “She wanted champagne, and we had a bottle of champagne with her.”

The party helped put Oil Can Harry’s back on the map.

“The party made the papers all around the world,” Young says. “All of a sudden, everybody was back at the club. It was jammed, jammed packed. The Saturdays went haywire.

“It wasn’t always full before the Grammys. But when we did the Grammy party, it became superstardom,” Young says. “There were lines up the street.”

Celebrity customers

Over the years, many celebrities stopped by the club to take country line dancing lessons or to hang out and dance the night away, including Genna Davis, Demi Moore, Reese Witherspoon, Joaquin Phoenix and Amy Adams when they worked together on “The Master,” Greg Louganis, and Vanessa Williams.

Before the “Drag Race” series became mega popular, RuPaul, who loves country line dancing, would frequent the club, Young says.

At the end of the first or second season of the series, RuPaul hosted a private cast party at the venue.

“He came in dressed in a cowboy outfit with a big cowboy hat,” Dominguez says. “RuPaul loved his country music.”

Editor’s note: The article has been updated to reflect Bob Tomasino and John Fagan’s ownership roles in Oil Can Harry’s, and Tommy Young’s employment history.