Bayard Rustin, left, and Walter Naegle were a couple more than 40 years before marriage equality was conceivable, but they wanted to legalize their relationship to have the rights afforded to heterosexual couples. They found that legal protection, such as being allowed hospital visitation or inheriting a deceased partner’s estate, in adoption. Photo: Estate of Bayard Rustin.

Bayard Rustin, the architect behind Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington in 1963, was not only a mastermind of nonviolent protests, but also a genius at legal maneuvering in his personal life.

RELATED: Bayard Rustin mentored Martin Luther King Jr.

INTERGENERATIONAL LOVE STORY

In 1977, Rustin, who identified as gay and had been marginalized in the Civil Rights Movement because he refused to live in the closet, met Walter Naegle. They lived more than five years in adjacent neighborhoods in New York City, but had never crossed paths until a fortuitous encounter at a traffic light in Times Square.

Rustin was 65, and Naegle was 27.

Their intergenerational love story is the subject of the short documentary “Bayard & Me,” which will be screened at the Long Beach QFilm Festival September 10.

RELATED: Long Beach’s QFilm Festival announces 2017 lineup

This year marks the 30-year anniversary of Rustin’s death. He died August 24, 1987 at the age of 75.

GENIUS LEGAL MANEUVER

Rustin and Naegle were a couple more than 40 years before marriage equality was conceivable, but they wanted to legalize their relationship to have the rights afforded to heterosexual couples. They found that legal protection, such as being allowed hospital visitation or inheriting a deceased partner’s estate, in adoption.

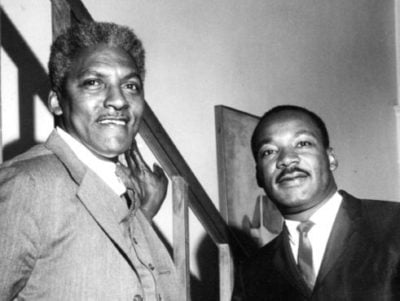

Bayard Rustin, left, was the architect behind Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington in 1963. King, right, also was mentored by Rustin. Photo: Monroe Frederick/Courtesy of the Estate of Bayard Rustin.

In 1982, Rustin adopted Naegle. They were among a handful of gay couples who had accomplished this genius legal maneuver. Nine years earlier, in 1971, renowned Hollywood architect John Elgin Woolf adopted his younger lover, Robert Koch.

In separate interviews with Q Voice News, Walter Naegle, 67, talks about his first meeting Rustin, the adoption idea and his mother’s reaction, while director Matt Wolf explains the intersectionality of Rustin and Naegle’s relationship and a different type of story about gay history.

Here are some excerpts.

Traffic signal meeting

“We were both waiting at the stop light at Times Square, at the corner of 42nd Street and 7th Avenue, to cross the street. We both looked at each other. He said, Hello. I’m Bayard Rustin, and we crossed the street together,” Naegle said. “From my interest in the Civil Rights Movement, I did know who he was. It was serendipitous or kismet that we met. I had lived in my neighborhood about five or six years, but our paths had never crossed. It was good luck. We were both very lucky.”

After crossing the street together

“It was afterwork. He asked me to come over for a drink, and I went over,” Naegle said. “He had just come back from Memphis and a demonstration for furniture workers with Mrs. Martin Luther King Jr. We talked about the demonstration, and he asked me about my life. There was a vibe. I feel in love with him.”

The intersectionality

“I was amazed there was this line of continuity with the civil rights movement, intergenerational gay couples and the gay rights movement,” Wolf said.

Different gay history story

“I wanted to tell the scope of the love story and the connection with the civil rights movement and the gay rights movement,” Wolf said. “This merited a more intimate telling version of the film that is told through Walter’s voice.

“It’s a love story,” Wolf said.

Mom meets Bayard

“My mom had met Bayard. He came to family gatherings and parties. She knew we were involved. She was fine with it,” Naegle said.

“A key test was when the adoption was in process. She had to sign a paper disowning me, so we had to confront it head on,” he said. “She said, Do you love him? I said, yes. That was all that mattered to her and to me.”

Intergenerational relationship

“It was a non issue. The only time we talked about it was when we didn’t know how much time we would have together,” Naegle said. “Bayard was very youthful. He loved to dance. He was a good dancer.”

Adoption idea

“It was Bayard’s idea. I thought it was clever. I was willing to try it,” Naegle said. “I felt very secure in my relationship with him, but the legal protections weren’t there, visitations in the hospital, making medical decisions.”

Adoption idea, part 2

“What was interesting was that the adoption was used a sly or subversive way to go around the law. It was legal mischief,” Wolf said.

“Bayard was a mastermind of protesting in the streets, and in private he also was a genius at the legal maneuvering,” Wolf said. “They were trying to protect themselves. They were doing something innocuous. The social worker was sympathetic to their cause.”

Social worker

“You just don’t know. The social worker could have their own biases,” Naegle said. “It was clear the social worker knew what was happening. There was just one interview, and she made a recommendation.”

Bayard Rustin, left, and Walter Naegle were a couple more than 40 years before marriage equality was conceivable, but they wanted to legalize their relationship to have the rights afforded to heterosexual couples. They found that legal protection, such as being allowed hospital visitation or inheriting a deceased partner’s estate, in adoption. Photo: Estate of Bayard Rustin.