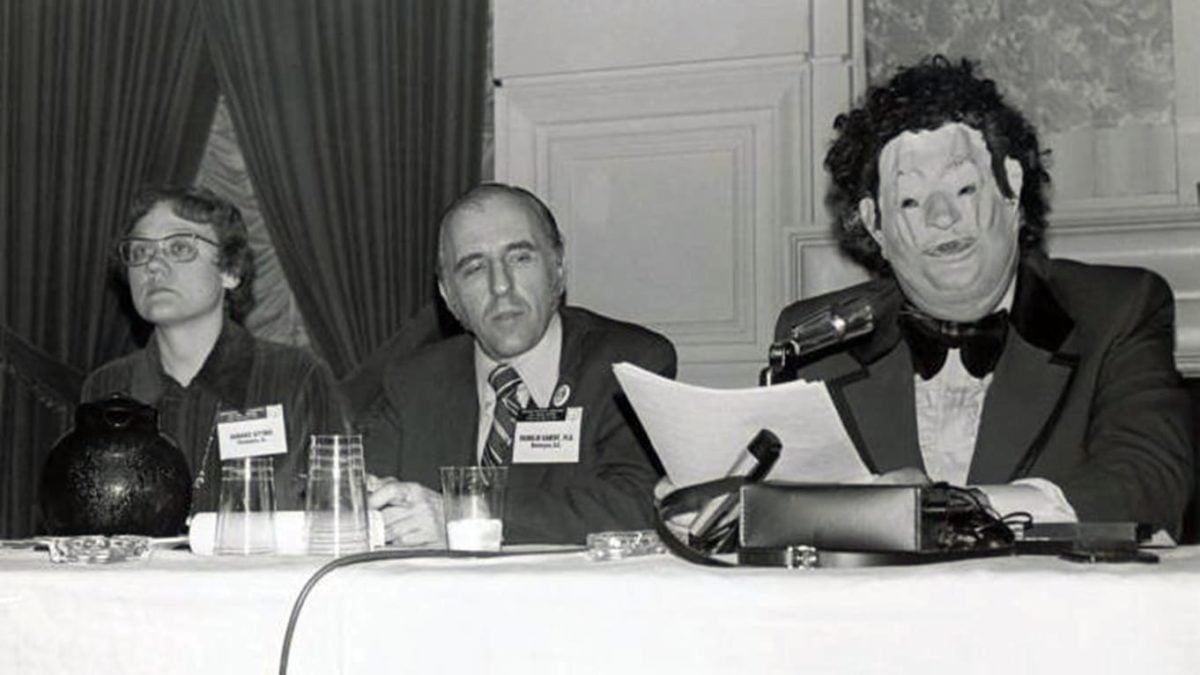

In 1972, Dr. John E. Fryer made history when he spoke on an American Psychiatric Association panel and told the audience, “I am a homosexual. I am a psychiatrist.”

Fryer, who feared losing his medical license, was disguised in a mask and used a voice modulator and introduced as Dr. Henry Anonymous.

At the time, homosexuality was classified as a mental illness, but Fryer’s testimony was a game changer. At its annual meeting the following year, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental illness. In other words, gays and lesbians were no longer classified as deviants.

Fryer eventually revealed he was the man behind the mask.

Fryer’s story will be told in “217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous,” which will be staged at UCLA’s Freud Playhouse tonight and Saturday. Fryer isn’t represented on stage. Actors playing three different characters in his life, serving as spirits, guide the audience through Fryer’s life.

‘The Lavender Scare’ documentary shows gay witch hunt by US government

John E. Fryer

Though largely invisible to the public, Fryer is one of the most important people in LGBTQ history. To say his contributions have been vital and paramount in the fight for equality would be an understatement, said Ain Gordon, who wrote and directed “217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous.”

“It’s a lynchpin in the movement. As long as psychiatrists said gay people were deviant, you could be discriminated against,” Gordon said in an interview with Q Voice News.

“You couldn’t ask for equal protection under the law when you are deviants. You can’t say that the police can’t raid a gay bar if the patrons are deviants,” Gordon said. “You’re not a citizen. You’re a criminal.”

Dr. John E. Fryer, right, disguised as Dr. Henry Anonymous, speaks on a 1972 panel at the American Psychiatric Association. Lesbian activist Barbara Gittings, left, and gay activist Frank Kameny, middle, also participated on the panel. Photo: New York Public Library Digital Collection.

Dr. Henry Anonymous

Fryer was invited to the 1972 panel, “Psychiatry: Friend or Foe To Homosexuals?,” by pioneering gay and lesbian rights activists Barbara Gittings and Frank Kameny. They wanted to overturn the federal government’s ban on gay and lesbian employees and the American Psychiatric Association’s classification of homosexuality as a mental illness.

Gittings and Kameny had invited about a dozen psychiatrists to speak, but they all rejected the invitation because a requirement was that the person had to publicly say they are gay.

When Gittings and Kameny agreed with Fryer to let him wear a mask, Fryer accepted.

Gordon, who didn’t know Fryer’s legacy, discovered the masked man by accident. In 2014 and 2015, Gordon had a residency at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia to research his yet-to-be-determined next project.

Amongst the Historical Society’s almost 20 million material items, Gordon came across a copy of Drum, a 1960s Philadelphia gay magazine, which mentioned Gittings.

That discovery motivated Gordon to further research online about Gittings, which eventually lead to a 1972 newspaper photo of Fryer, disguised in his mask, sitting next to Gittings and Kameny on the American Psychiatric Association panel.

Making LGBTQ history

Shortly thereafter, Gordon found out that the Historical Society housed Fryer’s personal papers — 217 boxes worth of material. Gordon immediately started his research.

“Right away what interested me was that he had done this incredibly important thing in a mask,” Gordon said. “Many people don’t know him or know his real name. Somehow he has stayed behind the mask. He had a big ego, but he never staked claim to the moment. He never sought the fame.

“The mask is more famous than the man in it, which seemed like a metaphor for queer history,” Gordon said. “So much queer history has been undercover or in the closet. We are looking behind a public persona to find that history.”

Fryer, who died in 2003 at 65, had a 30-year career at Temple University as a professor. Fryer was also one of the first psychiatrists in Philadelphia to treat patients with HIV and people with AIDS related bereavement issues.

The APA’s highest civil rights award is named in Fryer’s memory.

In 2017, a historical marker in Fryer’s name was unveiled across from the Historical Society.