For the gay patrons of the Black Cat tavern in Silver Lake, it was a rotten way to start 1967.

But the horrific events of that night inspired a gay political organization that adopted a defining word for the LGBTQ+ community.

As New Year’s Eve celebratory balloons fell from the ceiling at midnight on Dec. 31, 1966, undercover officers with the Los Angeles Police Department tore Christmas decorations from the walls and brandished their guns.

They attacked and handcuffed 14 people inside the neighborhood gay bar.

Two men arrested for kissing were forced to register as sex offenders.

Two Black Cat patrons escaped to another nearby neighborhood gay bar, New Faces. But police officers chased them, assaulted the bar’s owner, and beat her two bartenders unconscious.

One of the bartenders suffered a ruptured spleen from the police attack.

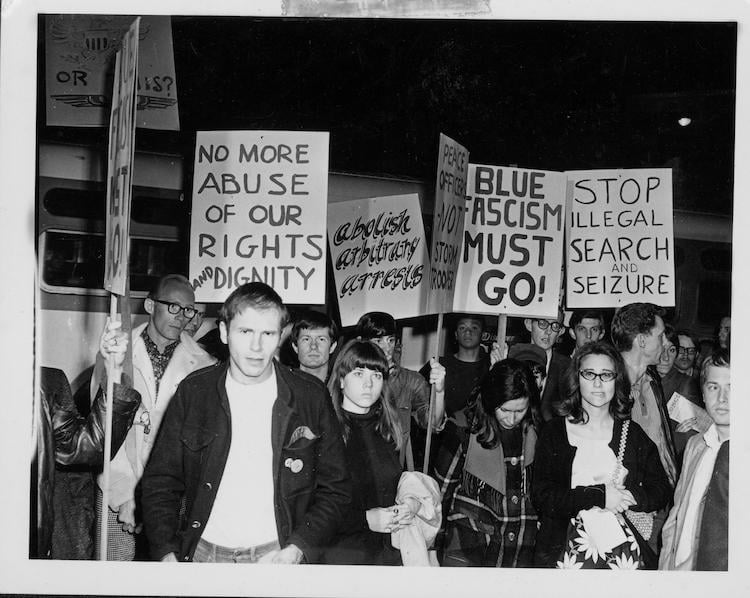

The gay-political activist group PRIDE (Personal Rights in Defense and Education) lead hundreds of people in protest after the Los Angeles Police Department raided the Black Cat bar in Silver Lake and brutalized patrons and the bartender. Feb. 11, 1967. Photo: ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

Black Cat protest

Violent police raids on gay bars were common in the 1960s not only in Los Angeles, but also across the county.

But this time, the gay community fought back.

On Feb. 11, 1967, and for several days after, more than 200 people peacefully marched at the Black Cat on Sunset Boulevard while heavily armed police hovered nearby watching them.

They protested not only the Black Cat raid, but also the Los Angeles Police Department’s broader campaign of routine harassment, terror, and brutality at LGBTQ+ establishments throughout the city.

The demonstrators also demanded the police end their abusive tactics. The department, however, refused to stop their terror campaign targeting gay citizens.

P.R.I.D.E.

The Black Cat demonstration was organized by a gay activist group called Personal Rights in Defense and Education, also known as P.R.I.D.E., that formed in 1966 by Steve Ginsburg.

This use of the word Pride in connection with gay activism is one of the earliest documented cases.

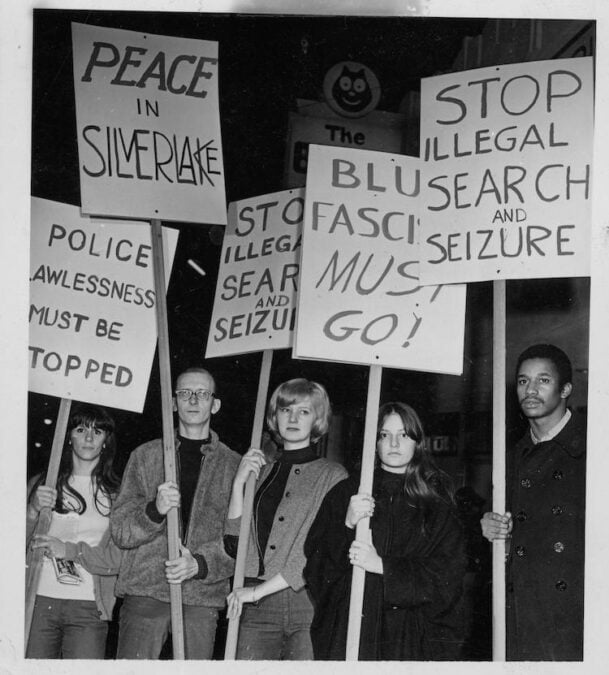

From the beginning, P.R.I.D.E. was more confrontational than the pre-1960s gay rights groups. The group’s goal was to get into the streets and get in the faces of the opposition with noisy, loud demonstrations and political action.

The group’s meetings were called “PRIDE nights” and took place at the gay bar The Hub. Like many gay bars, The Hub served the community not only as a safe space to socialize, but also as a place to host and organize political events.

Also, Ginsberg often used the bar and club scene to connect with gay youth directly. P.R.I.D.E. defended gay bars and gay youth culture who attended them.

From the beginning, P.R.I.D.E. was more confrontational than the pre-1960s gay rights groups. The group’s goal was to get into the streets and get in the faces of the opposition with noisy, loud demonstrations and political action. Photo: ONE Archive at the USC Libraries

Historic protest, P.R.I.D.E. legacy

The Black Cat protest was the site of one of the nation’s first organized LGBTQ+ demonstrations. It was more than two years before the New York’s Stonewall Uprising in 1969.

This landmark demonstration — along with numerous others in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Philadelphia, and across the country in the mid-1960s — helped launch the gay civil rights movement.

In September 1967, P.R.I.D.E. published a newsletter, The Los Angeles Advocate.

Two years later, it transformed into a nationally distributed magazine known today as The Advocate.

P.R.I.D.E. dissolved in 1968, but its legacy endures.

Following the Stonewall Riots in 1969, LGBTQ+ communities in cities across the nation organized marches and protests as a way not only to pushback against decades of discrimination and violence, but also inspire a growing gay civil right movement.

Initially, they were called “Gay Freedom Marches” or Gay Liberation Marches.”

In 1973, it appears that Minnesota gay rights activist Thom Higgins helped create “Gay Pride” for a banner and slogan to chant to supporters and bystanders during a march protesting anti-gay comments by The Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis.

It’s one of the earliest documented uses of the slogan “Gay Pride.”

In the following years, such marches and celebrations, organized by LGBTQ+ people, spread across the county. Their mission was to not only demand fair and equal treatment, but also come out of the closet and celebrate their right to exist without fear of persecution.

The LGBTQ+ community eventually identified these events as Gay Pride parades.

Pride is as relevant today as it was 55 years ago when those brave activists demonstrated on Sunset Boulevard and told the Los Angeles police that they had a right to exist without the fear or persecution.

It was an early example of what would later be a rallying cry of ‘Out of the bars and into the streets.’