Robert Gamboa attends the unveiling of the two Pride-painted lifeguard towers at Ginger Rogers Beach on Saturday in Santa Monica. Photo: Robert Gamboa.

The history of Ginger Rogers Beach came out of the closet Saturday morning.

Two Pride-painted lifeguard towers were unveiled with signs detailing how Gingers Rogers Beach has served as a safe space and destination for LGBTQ+ activism dating to the 1940s.

The unveiling of the lifeguard towers took place as part of LGBTQ Pride Month.

“Ginger Rogers Beach has been in the shadows of Los Angeles history for too long. Today, we celebrated the important legacy of this beachside sanctuary, and welcomed two striking visual symbols of inclusion and love with the Progress Pride lifeguard towers,” said Los Angeles County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath, who represents the Third District, where the beach is located, and sponsored the motion in May to have the area designated.

Towers 17 and 18 on Will Rogers State Beach are just north of the Annenberg Community Beach House in Santa Monica. The stretch of beach located between the towers is Ginger Rogers Beach, a section just south of the intersection of Pacific Coast Highway and Entrada Drive, that also is known as Los Angeles gay beach.

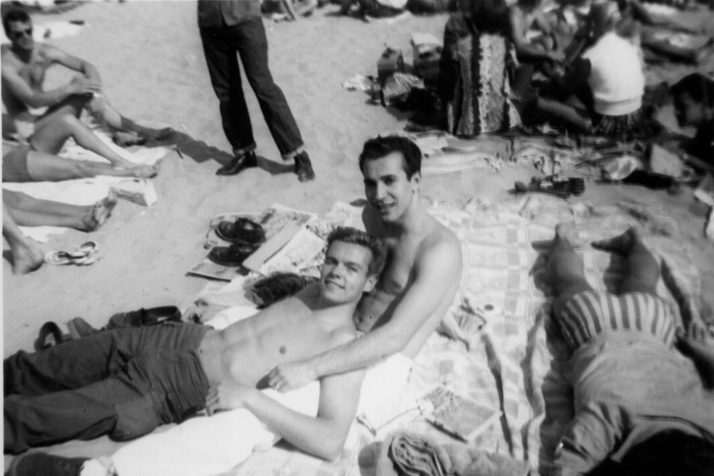

Pat Rocco relaxes with a friend at Ginger Rogers Beach in Santa Monica. Photo: ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

The ONE Archives Foundation, the nation’s largest and oldest LGBTQ+ history organization, extensively researched the vibrant history of Ginger Rogers Beach for this project.

“LGBTQ+ folks have been flocking to Ginger Rogers Beach since at least the 1940s. This golden strip of sand where legendary activist Harry Hay, in 1950, gathered 500 signatures opposing McCarthyism; where “Berlin Stories” writer Christopher Isherwood, in 1952, met painter Don Bachardy; and where the groundbreaking drag queen, Jose Sarria, on a visit from San Francisco in 1957, gave an impromptu performance on the sands. Ginger Rogers Beach is steeped in queer history,” Tony Valenzuela, executive director of the ONE Archives Foundation, said at the unveiling.

“When visitors see the lifeguard towers painted rainbow, I hope they think about the generations of LGBTQ+ people who have found safety and camaraderie here,” Valenzuela said.

Here are six other bits of queer history that the ONE Archives Foundation’s Trevor Ladner, education programs manager, discovered about Ginger Rogers Beach.

- In 1950, Harry Hay and Rudi Gernreich gathered 500 signatures at Will Rogers State Beach for a petition opposing the Korean War and McCarthyism. At this time, gay beachgoers were not yet willing to join an organization to discuss homosexual rights.

- In 1995, Hay wrote: “Forming a society of two, and determined to get a discussion group going, (Rudi and I) went to an unmarked section of Santa Monica Beach that we knew was frequented by gay brothers… By the end of the summer, we had gotten 500 signatures on our petition, and had found not one person who would dare come to our (homosexual) discussion group, so overpowering was the terror of police reprisal or blackmail.”

- The following year, Hay led the formation of the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles, one of the nation’s first gay rights organizations. The group argued that gay and lesbian people were a minority group oppressed by a prejudicial society and needed to organize in order to challenge their unjust persecution.

- Police vice patrol began terrorizing on queer beachgoers at Will Rogers State Beach as early as the 1950s, as reported in Santa Monica’s Evening Outlook. Under Police Chief William Parker – called “Wild Bill Parker” by the gay community – and criminal psychologist Paul de River – who believed that gays presented a danger to children and society – the Los Angeles Police Department targeted homosexual behavior and cross-dressing at bars and public spaces in the 1950s and 1960s through a dedicated vice squad.

- LAPD vice officers in plain clothing would often target gay men by inviting or coercing perceived homosexuals to perform intimate or sexual acts at bars or public restrooms; whether these men took the bait or not, the officer would perform an arrest upon any indication of interest. Queer women were often targeted for dancing together at bars or wearing masculine clothing in public. In addition to jail time on felony offenses, it was common for queer people who were arrested to lose their jobs or careers, and to suffer from depression or alcoholism.

- In 1970, The Advocate– the first national gay newspaper, founded in Los Angeles in 1967– warned its readers of a “minor league” plainclothes vice squad stationed at Will Rogers after a gay man reported being entrapped, arrested, and charged with lewd conduct by the West Los Angeles Police Division. The following month, they again warned readers that arrests continued to be made at this location, describing it as a “hot spot” for being terrorized by police.

- On Independence Day, 1976, queer beachgoers and allies took a stand in the face of LAPD bullying and harassment “with a magnificent display of courage and unity.” Reportedly, 2,000 people were gathered at Will Rogers Beach to celebrate the July 4 holiday. When vice officers pulled two gay men out of the water and began beating them with batons, onlookers fought back, crowding around the officers in an attempt to dissuade them and eventually “pelting the cops with stone, sand, cans, and seaweed.” When one woman attempted to help one of the beaten men, she was thrown to the ground and run over by the police jeep, needing to be hospitalized for leg injuries. The Los Angeles Times reported on the incident, in addition to other local and national publications, noting that several involved suffered minor injuries.

- Two years after the incident, Don Amador— an appointed gay community liaison for Mayor Tom Bradley, the first position of its kind in the nation— worked with local elected officials to have homophobic graffiti removed from a structure at Ginger Rogers Beach.