Sarah-Joy Ford, left, is the artist behind the exhibit “Looking for Lesbians.” It was inspired by the ONE Archives lesbian pulp collection. Alexis Bard Johnson, right, curated the show. Photos: Alexis Bard Johnson.

In a new exhibit, “Looking for Lesbians,” created for ONE Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries, artist-in-residence Sarah-Joy Ford and curator Alexis Bard Johnson explore how pulp novels gave rise to lesbian literary culture.

“Tracing that relationship and the networks that form in and out of that publishing community, I think that’s something we’re both really interested in,” Johnson told The Advocate. ‘It’s something that Sarah-Joy has really effectively traced in the months she’s been here in residence in Los Angeles.”

Sarah-Joy Ford is an artist and post-graduate researcher at Manchester School of Art, where she is a co-director of the Queer Research Network Manchester and a member of Proximity Collective. Her Ph.D. research explores quilt making as an effective methodology for re-visioning lesbian archival material.

‘Work for a Million,’ pioneering lesbian pulp fiction, gets graphic novel makeover

Opening

“Looking for Lesbians” opened July 23 at the ONE Gallery in West Hollywood, featuring Ford’s artwork alongside selections from ONE’s lesbian pulp fiction collection and other archival materials related to lesbian literature in Los Angeles. “Looking for Lesbians” is set to run throughout the rest of the summer, closing Sept. 10.

Lesbian pulp fiction

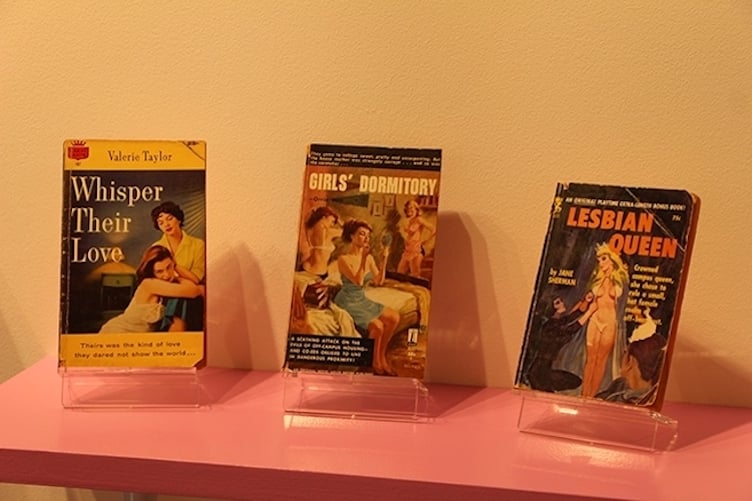

Lesbian pulp novels are a form of literature that grew from the 1950s and 60s, when the LGBTQ+ community was part of a growing counterculture that was still outlawed by mainstream society. Marketed with pin-up cover art and taglines about forbidden love and seduction, these cheap paperbacks sold at drugstores or ordered through the mail were often the only available novels about lesbian women. Popular authors included Valerie Taylor, Vin Packer, Ann Bannon and Orrie Hitt.

Discussing Ford’s residency with ONE Archives, Johnson suggested the organization’s collection of these books as a starting point, as it was often overlooked in favor of literature aimed at gay men. “There’s a size discrepancy between gay male pulps that have been published versus lesbian pulps, especially lesbian pulps meant for a lesbian audience, written by women or lesbians, rather than written for a male gaze or heterosexual gaze,” she said.

These three lesbian pulp fiction books are part of the ONE Archives collection and helped inspire the “Looking for Lesbians” exhibit.

Textile meets digital

As a textile artist, Ford used the source material and stories from people behind the archives as inspiration for drawings and watercolor paintings, which then became digital patterns for fabric printing, quilting and embroidery.

‘That’s what I enjoy, that shifting between the digital and the physical space, and thinking about all of these things as collectively handmade. It’s all an accumulation of small gestures. Even when you’re creating embroidery designs on a computer it’s still handcraft in a way.”

The resulting art exhibit explores the network of lesbian readers and writers that developed around these books in the Los Angeles area. “What came out of the pulp novels is the beginning of a huge shift in terms of lesbian literature and women. I was interested in how lesbians were seeking those things out and communicating them through bibliographies, book reviews, lesbian publications, and then eventually the development of presses, bookshops and communities around literature.”

Forbidden love

While lesbian authors of the 1950s and 60s wrote stories celebrating their identities and relationships, they were frequently subject to government censorship because the novels were mailed through the U.S. Postal Service.

“The novels have to be able to be sold and they need to make a profit, so they have to end tragically for the lesbian in some way shape or form. It can’t celebrate lesbianism or a homosexual lifestyle,” Johnson explained. “But what comes out of that are smaller presses that don’t have the same kind of guidance because it’s later in time, or they’re not being sent through the mail in the same way.”

‘Spring Fire’

One of Ford’s biggest inspirations in “Looking for Lesbians” was “Spring Fire” by Marijane Meaker, who wrote under the pseudonym Vin Packer. Meaker reflected on the censorship of lesbian literature in the Cleis Press reprint of the book, and in the new documentary “In Her Words.” “She’s actually spoken about how she wrote one ending, and then when she spoke to her editor he said to get it published (the characters) have got to be older, so in university and sorority, and it’s got to have a tragic ending,” Ford said.

At the time, the best authors could hope for was a story with an ambiguous ending like “The Price of Salt” by Patricia Highsmith, which inspired the 2015 film “Carol.”

‘Pulp novels weren’t ambiguous. (Lesbians) were either put in an asylum, died in a car crash, or got married. Whereas the ambiguous ending in the 1950s, it was pretty lucky that it sneaked through.”

Choose your own adventure

Censorship of lesbian literature forced readers to be careful and creative in how they engaged with it. For instance, Johnson said there are rumors that women would circulate information about where to stop reading the book if they wanted to skip the tragic ending.

“I can only imagine that people then imagined a happy ending, a kind of fan fiction before fan fiction,” Johnson said. On the down low, if you don’t want to read about so-and-so’s suicide or having to marry a man, just stop here and enjoy the first part.’”

“People were finding ways to get what they needed out of those books,” Ford added. “That eventually gave them the kind of prompt for people to be creating their own ways and finding ways around censorships, by creating their own literary cultures and communities.”

Underground networks

The subversive culture that grew around lesbian pulp fiction gave queer women a new way to find each other and form relationships without getting caught.

“It becomes a code: Have you read ‘Spring Fire’? If someone’s like, yes, or, I know what that is, that’s a kind of new version of Friends of Dorothy for women,” Johnson said.

This carried over to early LGBTQ+ magazines and newsletters like Vice Versa, published in Los Angeles in 1947-1948.

“Lisa Ben only made 13 copies of each issue of Vice Versa because she was doing it on a mimeograph, and at the bottom would basically be like, After you’re finished reading this please circulate to others who might be interested. There’s a whole circulation network that we can’t really trace, with both the pulps and the magazines.”

The exhibit

Visitors to the “Looking for Lesbians” exhibit in West Hollywood can expect a visual, immersive experience with ONE Archives materials and Ford’s artwork.

“To me it’s really representative of an artist’s several-month residency at ONE, starting with the lesbian pulps as a center point and then really branching out to LA literary culture and lesbian culture, writing and publishing,” Johnson said. “It takes that into unusual forms in terms of transforming the entire space, with wallpaper, with quilts, with a huge map that traces Sarah Joy’s own experience mapping out this history.”

Changing the narrative

Ford said that the focus of her work around lesbian pulp fiction wasn’t about removing the limitations of the genre, but rather acknowledging it as a prompt for growth and literary activism.

“It wasn’t a rewriting of a sad ending into a happy ending,” she said. “It was more of a continuation of this practice of taking those novels, taking the queer culture from the time that it’s in, taking what you need from it, and building a new culture out of that. I think that’s so much of what the history of lesbian culture and queer culture has been.”

ONE Archives

“Each encounter with the archive is deeply personal and entangled, and it’s communicating in a way that the archive is also all those people that built it,” Ford said.

“I hope it’s a reminder that the archive is a place that everyone is welcome to go into and negotiate,” she said. “The archive is kept alive by the people who donate their materials and are still connected with them. There are communities of people attached to the archive, to ONE and to the material.”

This article originally appeared on Advocate.com, and is shared here as part of an LGBTQ+ community exchange between Q Voice News and Equal Pride.