Thursday marks the 55th anniversary of an important, but little known milestone in gay history.

On Aug. 17, 1968, Long Beach resident Lee Glaze, owner of the Wilmington gay bar The Patch, took a stand and pushed back against the Los Angeles Police Department’s constant harassment of his gay male customers.

Glaze’s resistance is significant because it’s an early example of the gay community protesting against police abuse and took place 10 months before the Stonewall Inn demonstrations in New York.

For some people, the national awakening on gay civil rights started at Stonewall. Glaze’s courage, however, shows the struggle for LGBTQ equality was born before Stonewall.

In this 1968 photo, patrons from The Patch, a gay bar in Wilmington owned at the time by Long Beach resident Lee Glaze, hold bouquets of flowers outside the Los Angeles Police Department Harbor Station during a “flower power” protest against police harassment. The protest is a significant milestone in gay history because it took place one year before the Stonewall Inn riots Rebellion in New York City, which some people think was the dawn of the gay civil rights movement. Glaze, with blond hair, is holding bouquets and looking to his right. Photo Q Voice News.

Lee Glaze was bravery

“Lee Glaze was brave enough to step forward,” Michael Oliveira, an archivist with ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, told Q Voice News in 2017. “His contributions led to the growth and progress in gay rights that we are all enjoying today.”

Lee Glaze’s actions earned him a place on Memorial Wall at Harvey Milk Promenade Park in Long Beach.

In Glaze’s case, he refused to comply with LA’s prejudiced law that outlawed same-sex couples from dancing in public.

The LA ordinance outlawing same-sex dancing was passed July 2, 1958, and more than 10 years later, Glaze was relentless in fighting it.

Glaze fought the law with bravery and a campy sense of humor.

Morris Kight home named historic monument by LA City Council

Lee Glaze fought discrimination

The LA police department’s undercover vice squads targeted the city’s gay and lesbian bars to make sure the obviously prejudiced law was being followed.

If it was ignored, the police had an established practice of terrorizing and arresting gay and lesbain customers.

Glaze, however, was one step ahead of the dancing police.

If Glaze spotted any covert officers at The Patch, he would yell a campy code to warn his customers, who knew the secret phrase.

‘God save the queen’

“God save the queen,” Glaze would holler.

That warning also helped make Glaze a gay-rights pioneer who fought for equality.

Glaze, known as “The Blonde Darling,” was a larger than life character with a campy personality, recognizable chuckle, and short blond hair.

LA Pride 2017: Alexei Romanoff, original Black Cat protester, named grand marshal

Glaze had been warned by officers that if he didn’t want the police to close his Harbor-area gay bar, which was a quick drive from neighboring Long Beach, he had to follow the rules.

On Aug. 17, 1968, three undercover vice officers targeted The Patch and arrested two men for lewd conduct.

Witness to history

Their crime?

Troy Perry, a former Southern Pentecostal minister, visited The Patch that evening and witnessed the incident.

The two men were falsely arrested, Perry told Q Voice News.

The two men had been talking to each other, and one of them slapped the other on the butt, Perry said.

The men were jailed at the LA police department’s Harbor Station, and Glaze told the crowd at the bar that The Patch would post bail.

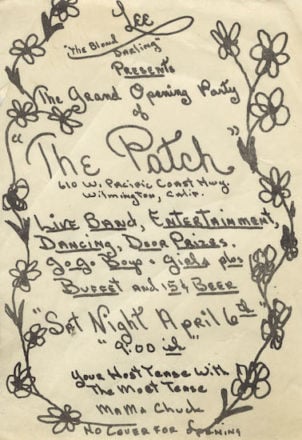

Lee Glaze opened his bar The Patch in Wilmington in 1967 with this flyer announcing the grand opening. Photo: Q Voice News.

‘Flower power’ protest

Glaze had an idea, Perry said. Glaze and about a dozen patrons went to a local flower store owned by one of the customers and scooped up every gladiola, mum, carnation, rose, and daisy in the shop.

‘Here to get our sisters’

Glaze and the demonstrators, including Perry, arrived at Harbor Station about 3 a.m.

“When we arrived at the police station, Lee told the officer at the desk, We’re here to get our sisters out,” Perry said. “The officer asked, What are your sisters’ names? When Lee said, Tony Valdez and Bill Hasting, the officer had this surprised look on his face and called for backup.”

While the demonstrators waited, they staged a “flower power protest,” said Perry, noting that the police were perplexed and speechless.

“They didn’t know what to do with all the gay men waiting in the lobby,” Perry said.

Six hours later, the two men were released.