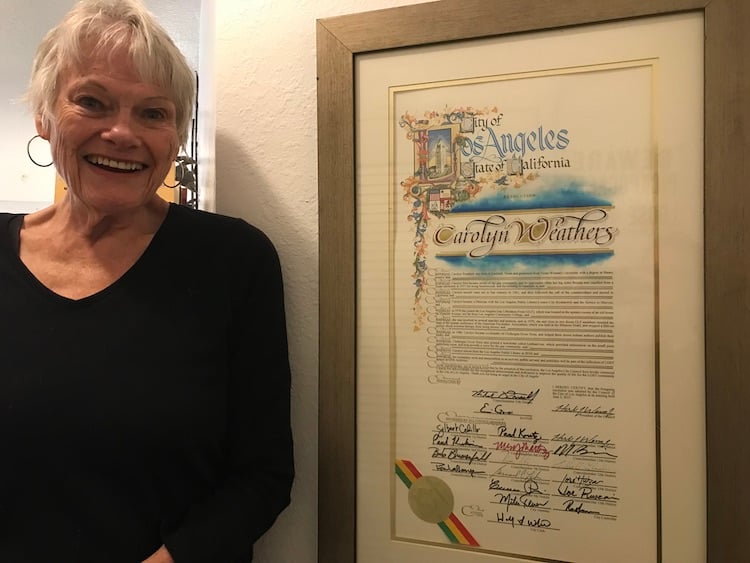

Carolyn Weathers, photographed on Jan. 12, stands next to the Heritage Award she received from the City of Los Angeles in 2015 for her work to improve the lives of the LGBTQ community. Photo: Q Voice News

Commentary

(LGBTQ Pride Month takes place in June, but for us at Q Voice News, we celebrate Pride 365 days a year. Q Voice News features a series of interviews and first person essays under the theme What Pride Means to Me. This essay is from retired librarian and lesbian activist Carolyn Weathers. This commentary also is significant because Dec. 15, 2023, marked the 50th anniversary of the American Psychiatric Association issued a resolution stating that homosexuality was not a mental illness or sickness. Carolyn Weathers participated in a 1970 demonstration that set those wheels in motion. She writes about participating in the “Biltmore Invasion.” Check out previous essays on What Pride Means to Me.)

What Pride means to me is that of a public, wonderful, and world-wide celebration of our multifaceted community, with the Pride parades a cherry-on-top celebration that grew from grassroots activism to become the iconic events they are today.

I’m proud of the people who paved the way. I’m proud of my big sister Brenda, who was expelled from college for “moral turpitude” homosexuality in 1957 when she was 20.

Brenda was handcuffed in a Denton, Texas, jail and told she could return to college if she renounced her homosexuality.

She refused to do that.

After being expelled, Brenda moved to Los Angeles and became a leading LGBTQ activist in the 1970s.

Her story is representative of the stories of countless others.

Coming out in 1961

When I came out in 1961, there was no Pride. We in the community had camaraderie, but only in each other’s homes or in the gay bars, which were subject to police raids.

We had no public display of Pride except during San Antonio’s annual Fiesta San Antonio, a twin to New Orleans’s Mardi Gras, and to Rio de Janeiro’s Carnavale, where people are allowed, even expected, to act outside the norms.

One of the celebrations is in La Villita, a historic Mexican village in the heart of downtown San Antonio. We had a place we called the “Gay Curb” where we met and acted just gay enough for people to assume we were gay. The light kiss on the cheek, the holding of hands. That was OK. It was Carnavale after all.

Moving to LA in 1968

Things were different in Los Angeles, where I moved in 1968, drawn there by the burgeoning counterculture and hippies.

Gay, feminists, lesbian-feminists, cross-dressing friends, and I performed impromptu guerrilla theater on Hollywood Boulevard, usually in front of the tour buses, and we got away with it, but not without angry shouts from some of the passers-by. Things might have been better in Los Angeles, but they had a long way to go.

I’m proud to have been part of the early movement that brought about change.

Protesting in LA in the 1970s

In 1970, the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front, of which I was a member, held the first Pride Parade in Los Angeles, in Hollywood. It was called the Christopher Street West Parade, named after the location of the Stonewall Inn in New York City.

I can’t describe the thrill of stepping out into the middle of Hollywood Boulevard and marching.

In 1971, the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front had a “Gay-In” at the merry-go-round in Griffith Park. Over 100 members of the community showed up. We sang, we danced, reveling in ourselves and who we were. “Free to Be, You and Me,” we shouted.

Even so, armed police watched us from one of the Griffith Park Hills.

Disrupting the American Psychiatric Association

Carolyn Weathers, center, stands at the podium inside the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles in November 1970. The American Psychiatric Association – which had classified homosexuality as a mental illness – was scheduled to show a movie that advocated curing gays and lesbians with electro-shock therapy during the trade group’s annual convention at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles. Weathers and approximately 35 men and women from the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front stormed the stage and canceled the screening in what became known as the Biltmore Invasion. That demonstration helped pave the way for the APA to declassify homosexuality as a mental illness or sickness. Photo: Provided by Carolyn Weathers.

In 1970, the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front disrupted a program of the annual American Psychiatric Association convention at the Biltmore Hotel in downtown L.A.

The program included a film showing how to “cure” homosexuals with electric shock aversion therapy. We took over the stage, stopped the film, and made the audience sit with us in small groups and talk, the first time such a discourse had taken place.

It set into motion the APA removing homosexuality from its DSM as a mental illness , in 1973.

Hooray, we were all magically and instantly “cured!”

Unfortunately, trans people were not included. More work to be done. There’s always more work to be done.

Police or not, the Pride bonfire had been lit, and there was no stopping it.

Fighting the zombies

The Civil Rights Movement in 1963 had lit a fire of social progress that inspired other oppressed groups to fight back.

Frank Kameny and Barbara Gittings marched with LGBTQ banners at the Capitol in Washington, D.C.

The Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis were formed.

The Women’s Center opened.

Jewel Thais-Williams opened L.A.’s 1st gay black nightclub Jewel’s Catch One

In 1973, Jewel Thais-Williams, a Black woman, opened Catch One, a nightclub on Pico Boulevard, one of the first safe spaces for everyone regardless of gender, race, or orientation.

An LGBTQ center in Houston.

A “Gay-In” in Seattle.

Over time, Pride marches and parades started in American cities. LGBTQ people with un imaginable courage work to set up Pride marches and community organizations.

All from small steps, one match lighting up another match.

Today, Pride enables LGBTQ people who are out in the world to thrive in their authentic selves. Pride reveals stepping stones to those who want to come out, but are hesitant for whatever reason. Just knowing that there is such a thing as Pride can offer some comfort to those who, for whatever reason, never come out with knowledge that Pride exists and flourishes.

Pride is a beacon of hope for a gay man in Brownfield, Texas, or Swaziland, or a lesbian in Provo, Utah, or Shanghai, a trans man or trans woman in Dade County, Florida, or Steubenville Ohio, even in progressive cities like Los Angeles or Austin.

The ultraright comes after us like a zombie horde. They just don’t stop. We don’t either. From the striking of one match in our past, that lit up another match and then another, we have a blazing bonfire.

The zombie horde keeps lurching toward us, but we keep stoking our Pride bonfire.